|

| Pit-to-pier terminus (Peninsula Daily News) |

The most recent poster child for this kind of screw the land and water operation was the abortive attempt by the international conglomerate Glacier NW to mine Maury Island and ship its gravel via shore side barges staged in a state aquatic reserve . After a decade-long battle waged by the local group Preserve Our Islands, actions by newly elected Lands Commissioner Peter Goldmark and the federal court held up Glacier NW long enough for a buy-out deal to be reached. ['State lawmakers approve funds to buy out Glacier Northwest gravel mine' ]

(Proud disclosure: Preserve Our Islands evolved into Sound Action on whose board I sit.)

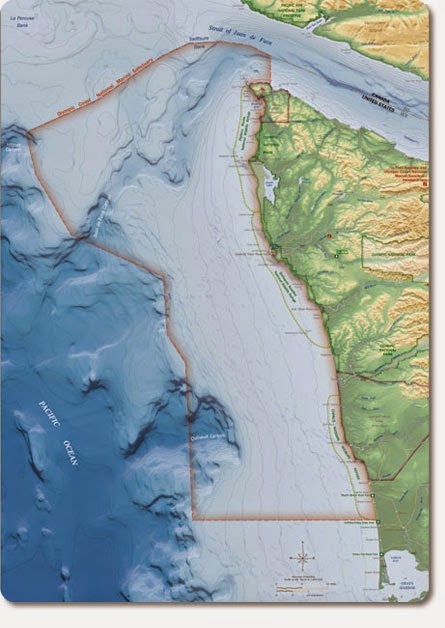

Whack-a-mole: Over in Hood Canal Fred Hill Materials had been pushing for years to build a four-mile conveyor belt system to send gravel mined from its Shine pit to a 998-foot pier in the undeveloped nearshore for barging. Fred Hill Materials ran into financial difficulty but the project burrowed back under the ownership of Thorndyke Resources and has been moving forward through the Jefferson County planning process. Many of us thought the permitting process would end when Lands Commissioner Goldmark and the U.S. Navy signed a conservation easement restricting industrial development in Hood Canal waters. ['Wash., Navy sign Hood Canal conservation easement'] Now we find the process alive as a deadline approaches for comment on the project’s draft Environmental Impact Statement.

The dEIS is found at the Jefferson County site and a county public open house will be held next Monday, August 4, 5:30-8 PM, at the Port Ludlow Bay Club, 120 Spinnaker Lane, Port Ludlow. Written comments with name and street address should be sent via email by 5 PM August 11.

John Fabian who leads the Hood Canal Coalition explained that, "when hundreds of millions of $$$ a year are out there in one’s fantasy world, people act in the most remarkable ways," meaning that the project proponents will not give up.

The Washington State-U.S. Navy easement restrictions will go to court and most likely be the subject of legislative action. If the agreement holds, the project dies.

The project proponent thinks the project will be allowed despite the conservation easement. Lands Commissioner Goldmark at the state Department of Natural Resources thinks not. ['Project manager: New state, Navy conservation easement for areas of Hood Canal won't halt pit-to-pier']

So the proposal to screw the land and the waters because there’s gravel in them thar hills continues until the project proponent withdraws the permit or lose in court or the legislature.

Well, let’s turn the screw the other way by standing for the land and the waters. Stand up, speak up, write on. It’s our turn now.

--Mike Sato